Ask the publishers to restore access to 500,000+ books.

Internet Archive Audio

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 916 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

We are proud to present a presentation about the Herero of Namibia, formerly known as Southwest Africa, from the German Sudwestafrika, between the years 1884-1915

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

obscured text on back cover inherent.

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

comment Reviews

6 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station03.cebu on October 12, 2021

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, From the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915 by Jackie Sibblies Drury

2015, Theatre Journal

Related papers

The performative function of sound and music has received little attention in performance theory and criticism and certainly much less so in studies of intercultural theatre. Such an absence is noteworthy particularly since interculturalism is an appropriative Western theatrical form that absorbs Eastern sources to re-create the targeted Western mise en scene. Consequently, a careful consideration of the employment of sound and music are imperative for sound and music form the vertebrae of Asian traditional performance practices. In acoustemological and ethnomusicological studies, sound and music demarcate cultural boundaries and locate cultures by an auditory (dis)recognition. In the light of this need for a more considered understanding of the performative function of sound and music in intercultural performance, this paper seeks to examine the soundscapes of an intercultural production of Shakespeare’s Othello – Desdemona. Directed by Singaporean Ong Keng Sen, Desdemona was a re-scripting of Shakespeare’s text and a self-conscious performance an identity politics. Staged with a multi-ethnic, multi-national cast, Desdemona employed various Asian performance traditions such as Sanskrit Kutiyattam, Myanmarese puppetry, and Korean p’ansori to create the intercultural spectacle. The spectacle was not only a visual aesthetic but an aural one as well. By examining the soundscapes of fractured silences and eruptive cultural sounds the paper hopes to establish the ways in which Desdemona performs absences and erasures of ‘Asia’ in a simultaneous act of performing an Asian Shakespeare.

Nordic Journal of African Studies, 2023

This contribution to the special issue on rethinking gender and time in African history (co-edited by Jonna Katto and Heike Becker) develops an argument about time and gender in African history in relation to historical sound recordings. Revisiting a case study from the Namibian sound archive I demonstrate innovative methodological strategies that open up new avenues of conceptual and theoretical thinking about gender and time in African history. Using the example of Nekwaya Loide Shikongo, a prominent woman from Ondonga in northern Namibia (the colonial 'Ovamboland'), and an epic poem on the deposed King Iipumbu yaShilongo that she performed in 1953, I discuss how gender was constituted and mediated in relation to colonial temporalities. The article presents a historical ethnography of how both the Christian mission's cultural discourse and the South African colonial administration's efforts to masculinize the 'native' political authority produced a gendered perception of Owambo women during the first half of the 20th century. However, it also demonstrates the performer's powerful, creative reappropriation of these discourses, which we can gauge by approaching the historical sound archive with a methodological strategy of 'close listening'. The argument thus extends to a broader reflection on the potential of historical sound recordings for challenging Eurocentric teleological narratives of gender and modernity. It also looks into the inherent limitations, and thus the opportunities and challenges, which the colonial sound archive presents for the development of decolonial methodologies in fields such as historical ethnography, cultural studies, and historiography.

SECAC Review

This expanded review discusses the exhibition ZERO: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s-60s at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. Focusing on role of time in their work, I historically contextualize the activities of the Zero group and ZERO network. I propose that, much like De Stijl, ZERO be understood as a multiplatform entity: it was a journal, the artists surrounding it, and an idea. I argue that the temporality of ZERO’s projects is that of bodies and vision in motion. The experience of spectatorship parallels that of minimal art. ZERO's projects markedly differ from the timelessness that typically characterizes the museum as well as the regimented temporarily of the commercial mass media.

Critical Arts, 2013

The concern about South African arts being-as Achille Mbembe claims-'stuck in repetition' can be challenged by examining developments in the performance arts which deliberately employ repetition. In these cases repetition is played with not just as a process of voiding or emptying out, but also to reconceptualise and embody historical and lived experiences. This can involve re-enactments of images, texts and theatrical styles which are worked upon and productively problematised through performance as a live event. In looking at the performance aesthetics of repetition, Diana Taylor's The archive and the repertoire (2003) provides a useful context, since Taylor's work straddles the disciplinary intersections between performance studies, anthropology and history. As point of departure, this article focuses on three works produced at the 2012 National Arts Festival, since the accumulation of new and not-new works viewed in quick succession offers scope for identifying aesthetic trends and shifts. Brett Bailey's Exhibit A, Yael Farber's Mies Julie, and Omphile Molusi's Itsoseng, for instance, demonstrate various aspects of an aesthetics of repetition. The embodied histories that are performed in these works throw up a number of paradoxes. However, the productions do not simply circulate performing bodies as empty aesthetic images, but as transmitters of cultural memory, as well as witnesses to states of profound transition that engage both performers and audiences alike. We have to wonder whether art in general, and photography in particular, has lost its historical power to give form to life, and has, instead, become subservient to repetition.-Achille Mbembe, 'The dream of safety' (2011) In an address at the 'Figures and Fictions' conference held in Cape Town in July 2011, Achille Mbembe lamented the fact that instead of the expected 'explosion of aesthetic boundaries' after apartheid, '[c]ontemporary South African art seems content to use the techniques of quoting, re-appropriation, and recombination'. He makes a similar point in response to Brett Murray's controversial portrait of President Jacob Zuma (Hail to the Thief 11), arguing that 'we are stuck in repetition', and that what is needed now are 'concepts with which to hunt the real'. He adds: 'We also need to disrupt and disorganise the archive' (2012: 11). Mbembe distances himself from anxieties about what constitutes 'the Real' 1 and draws attention to the way the work of art can act as a 'mask' for encountering lived historical realities and experiences. The function of the mask, as

Comparative Drama, 2012

Avra Sidiropoulou. Review of Time’s Journey Through a Room dir. by Okada Toshiki/chelfitsch. ROHM Theatre, Kyoto, 17 March 2016 (world premiere). Asian Theatre Journal, Volume 34, Number 2, Fall 2017, pp. 474-479 (Review). Published by University of Hawai'i Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/atj.2017.0033 https://muse.

Language & Communication, 2007

Kritika Kultura

127-133 <http://kritikakultura.ateneo.net> © Ateneo de Manila University K r i t i K A KUltUrA

The narrated present What does ‘now’ mean in the 21st century and can it continue to exist? I am proposing exploring the concept of the ‘now’ through the point of confluence of space and time, an interval that is a single isolated moment, the present, that pertains to the individual yet relates to a collective whole. It is both physical and mental. The past cannot be erased, either physically or as a perpetuated myth. Its palimpsest remains as an often unseen entity. Thus the space of the present can only be understood through the past. However, in the 21st century, a global present exists as oppose to the traditional spatially-confined ‘now’. There is a collapse of conventional time states due to globalisation, created by what Marc Augé would call the condition of the supermodern, an overabundance. (There are some disputes over whether globalisation is a modern day phenomena, notably Wallerstein). This excess contributes to a present, a now that is a continuous flow of information whereby knowledge is accessed readily rather than gained through empiricism. Thus it is my contention that the ‘now’ of the 21st century could be seen as less of an isolated moment more as a continuity of the past that flows seamlessly into the future, the present superseded by differing time states that relate to the world as a whole rather than to the single isolated moment. This has ramifications, for example, whose history is it now? This exploration however, will not ignore the site that inspired the discussion and the peculiarities of the particular island as a small, singular place. To fully understand this position, I will reference Henri Lefebvre who says that space cannot be understood without reference to its function which places the island and its histories in context. The Narrated Present will therefore look at ‘now’ as an ephemeral position that encompasses both space and time with locational insight.

Midway through the second volume of Art Spiegelman's comic novel Maus: A Survivor's Tale, Vladek, the Holocaust survivor, during a walk through a Catskills resort, explains to his son the procedure for Selektionen at Auschwitz, the terrifying periodic physical evaluations in which prisoners were sorted according to those who seemed capable of further performing slave labor and those who were too weak and therefore condemned to be murdered in the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau ( . "In the whole camp was selektions," Vladek begins in the first panel of a four-panel block. "I went two times in front of Dr. Mengele." In the next panel, he continues to narrate his experience in the selections: "We stood without anything, straight like a soldier. He glanced and said: FACE LEFT!" At the same time, Vladek is shown abruptly turning a quarter turn in the image that accompanies this narration; in effect, he is performing his role in the selection for his son, Artie, who stands aside to the left of the panel and watches the re-created spectacle, all the while recording Vladek's narration with a tape recorder that hangs from his shoulder. In the third panel of the sequence, Vladek continues to narrate his experience in the selections, quoting Mengele's order again to "FACE LEFT!" At the same time, he enacts the prisoner's compliance with the order, performing another obedient quarter turn. In the fourth panel, Vladek's explanation continues in a narrative box above the panel ("They looked to see if eating no food made you too skinny"), but here the survivor's reenactment of the selection during a walk through the country is replaced by a depiction of the original scene of the selection. Vladek is now no longer the aged narrator of a past experience, but the naked, emaciated prisoner who is first experi-Erin McGlothlin encing the scene of victimization and domination. He performs again a quarter turn, but in this panel it is not Artie who observes and records Vladek's story. Rather, a German camp official (according to Vladek's narration, Josef Mengele), a predatory cat to Vladek's hunted mouse, stands to the left and orders him to "FACE LEFT!" and at the same time records his evaluation of Vladek's physical condition on a clipboard. This last panel effects a visual break in the block of panels, for it suddenly transports the reader from a visual depiction of a present site of verbal narration of the past to a visual depiction of the narrated moment of the past itself. The visual seems to signify the abrupt chasm between past and present (a young, emaciated Vladek versus an aged, well-dressed Vladek), while Vladek's telling of the story appears to hold the two events together, linking the past and present in the process of narration. The comic book format of the scene, with its easily differentiated depictions of two separate temporal levels and two physical manifestations of the same character (young versus old), appears to clarify the disparities between the past and the present and to divide the two temporalities into distinct units in a much more visceral way than narration. For a novel about both the Holocaust past of the survivor and his present-day relationship with his son, Maus's use of visual images as a supplement to narration seems to be an ideal method for demarcating the differences between Holocaust experience and the contemporary lives of the survivor and his son.

VANGUARD SCIENTIFIC INSTRUMENTS IN MANAGEMENT, vol. 11, no. 2, 2015, ISSN 1314-0582, 2015

Phaselis: Disiplinlerarası Akdeniz Araştırmaları Dergisi, V, 2019

Hellebrant Institut, 2022

ARCE Virtual Meeting 2022, 2022

UIN khas, 2022

Laboratorio de Arte: Revista del Departamento de Historia del Arte, 2003

Journal of Mathematical Chemistry, 2007

Sağlık ve Hemşirelik Yönetimi Dergisi, 2016

Memorias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 2011

History Australia, 2017

JAAPA, 2017

Nature microbiology, 2018

Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 2006

Related topics

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Stage Excerpt: We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as South West Africa, From the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915

By Jackie Sibblies Drury – Published June 10, 2013

Elsewhere in this issue of The Appendix , we interview the writer Jackie Sibblies Drury about her play We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as South West Africa, From the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915 , which earned glowing reviews during its recent runs in Chicago and New York. Its plot is this: six black and white American actors attempt to make their own play about the imperial German genocide of the Herero people of South West Africa in the late nineteenth, early twentieth century. After a rapid-fire, surprisingly slapstick overview of the history, the play’s main body follows the well-meaning but often egotistical actors as they chafe at the primary source that they hoped might inspire their work: a cache of letters sent home by German soldiers.

It does not go well.

Sibblies Drury shared an excerpt of the play with The Appendix . In these two scenes, the actors attempt to adapt one of those letters—but then fight about it. The play barrels headlong to a fierce and upsetting conclusion, but in this excerpt, at least, tempers are not so frayed that the play isn’t still bitingly funny. A challenging balance of social criticism, racial violence, and inquiry into how deeply we can empathize with the dead, We Are Proud to Present is the breakout contribution of a new voice in American theater. We are grateful to Sibblies Drury for the chance to introduce it to The Appendix ’s readers.

In other words, we are proud to present it.

Characters:

Actor 6 / Black Woman Actor 1 / White Man Actor 2 / Black Man Actor 3 / Another White Man Actor 4 / Another Black Man Actor 5 / Sarah All are young, somewhere in their 20’s, ish, and they should seem young, open, skilled, playful, and perhaps, at times, a little foolish.

Scene: Presentation [1896]

WHITE MAN and SARAH are dominant in the presentation. The letter is filled with Romance and Yearning. There might be some distant representation of African bodies … but the love is fore grounded.

WHITE MAN Dear Sarah. We awoke before dawn again this morning. And walked, and walked, And walked until long after dark. We walk so much even when I sleep I dream of walking in the heat. There is so much heat here Sarah.

I saw steam rising from the shoulders of the man in front of me. It is so hot our very sweat is wrested from our bodies. I have never experienced such thirst as this. Dear Sarah, I beg you for a picture, of you in our garden, for a picture of you in a cool and living place. I will hold your picture to my lips and feel refreshed.

Scene: Process

ACTOR 4 Can I ask a question?

ACTOR 6 What is it?

ACTOR 2 Are we just going to sit here and watch some white people fall in love all day?

ACTOR 4 I wasn’t going to put it like that—

ACTOR 2 Where are all the Africans?

ACTOR 1 We’re just reading the letters. I’m sure we’ll find something that has some more context.

ACTOR 2 I think we should see some Africans in Africa.

ACTOR 1 And I think we have to stick with what we have access to.

ACTOR 2 No no no. This is some Out-of-Africa-African-Queen-bullshit y’all are pulling right here, OK? If we are in Africa, I want to see some black people.

ACTOR 6 He’s right. We have to see more of the Herero.

ACTOR 4 That’s all I was trying to say.

ACTOR 6 We need to see what—

ACTOR 4 We need to see Africa.

ACTOR 2 That’s what I’m talking about.

ACTOR 4 You know? These dusty old letters talking about this dusty old place—

ACTOR 2 Yes.

ACTOR 4 I want to see the live Africa.

ACTOR 2 Preach.

ACTOR 4 The Africa that’s lush—

ACTOR 2 Um—

ACTOR 4 The Africa that’s green

ACTOR 2 Well—

ACTOR 4 With fruit dripping from trees—

ACTOR 6 Dig into it.

ACTOR 2 But the desert—

ACTOR 4 Gold pushing its way out of the ground—

ACTOR 2 That’s not—

ACTOR 6 (to ACTOR 2) Shh—

ACTOR 4 And so many animals—

ACTOR 6 Yes.

ACTOR 4 Monkeys—

ACTOR 4 Gibbons—

ACTOR 4 Elephants and giant snakes—

ACTOR 6 Stick with it.

ACTOR 4/ANOTHER BLACK MAN And I hunt them.

ACTOR 4 adopts an “African” accent. It’s not ok.

ANOTHER BLACK MAN I hunt de lion. I hunt de jagua. I hunt de tiegah.

ACTOR 2 But—

ACTOR 3, 5, 6 Shhh.

ANOTHER BLACK MAN When I kill a tiegah I eat de heart of the animal while it beats.

“African” Drums begins, slowly, provided by ACTOR 6. The beat is felt in a count of 7 (1-2, 1-2, 1-2-3)

ANOTHER BLACK MAN I push my hands inside the animal, breaking apart bone and sinew, until I reach the heart and I pull it toward my heart, feeling the veins stretch and snap, wiping spurts of blood from my face.

By now, ACTORS 1 & 3 & 5, have found the beat also. Now it starts to grow.

ANOTHER BLACK MAN I barely have to chew, the heart is tender. I pull a fang from the animal’s mouth and add it to my necklace of teeth – another kill, another point of pride, another day I provide for my family. My family—we feast on the best parts of the meat, we feast, and women ululate

ACTOR 5 ululates.

ANOTHER BLACK MAN and dance with naked breasts

ACTOR 5 performs “African” Dance. Others join.

ANOTHER BLACK MAN in front of our fire. And they are all my wives, the women are all my wives and I take two of them to my bed, and I fuck both of the wives I took to bed and I make them both pregnant because we are all as dark and fertile as African jungle soil.

“African” Dance and Drumming and joy. ACTOR 2 breaks in:

ACTOR 2 Y’all need to stop.

ANOTHER BLACK MAN I have many children. Many Many Children.

ACTOR 2 For real. Just stop.

ACTOR 5 Keep going!

ANOTHER BLACK MAN Many children that I love.

ACTOR 2 STOP.

ACTOR 2 This isn’t that kind of Africa. Ok? We already Wikipediaed this.

ACTOR 5 Yeah, but—

ACTOR 2 We know it’s like desert: dry, hot, arid, barren. What’s he talking about tigers and palm trees

ACTOR 4 I was making the part my own.

ACTOR 2 Oh come on.

ACTOR 5 You don’t want us to do anything.

ACTOR 2 You can’t make the part your own so much that you ignore what’s actually there.

ACTOR 1 That’s not what he’s saying.

ACTOR 2 Oh really?

ACTOR 1 It’s not.

ACTOR 2 So why don’t you tell me what he’s saying.

ACTOR 5 Why are you always so angry all the time?

ACTOR 2 I know you didn’t.

ACTOR 5 What?

ACTOR 4 Guys I know that I don’t know everything about the Herero but— Will you listen? We have to start somewhere.

ACTOR 2 So start by being black.

**Jackie Sibblies Drury** is a Brooklyn-based playwright.

Elsewhere in this issue…

- 1. Letter from the Editors

- 2. Letters to The Appendix

- 3. Lieutenant Nun

- 4. The Double World: One Man’s Search for Meaning in the Seattle Public Library

- 5. The Phantom Punch

- 6. The Fourth Skull: A Tale of Authenticity and Fraud

- 7. Death of a Sailor: Chapter 2: The Hoaxers

- 8. Local History: Drumnadrochit, Scotland

- 9. Bespelled in the Archives

- 10. Showing His Monster

- 11. From the Aviary: Haliaeetus leucocephalus

- 12. Mother Machine: an ‘Uncanny Valley’ in the Eighteenth Century

- 13. The Many Lives of Ned Coxere: Were British Sailors Really British?

- 14. Spectral Passages

- 15. The Lady Vanishes

- 16. Woman Filing Her Nails

- 17. Andean Atlantis: Race, Science and the Nazi Occult in Bolivia

- 18. Stage Excerpt: We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as South West Africa, From the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915

- 19. Interview with Jackie Sibblies Drury: The Reenactors

- 20. The Woman in Green: A Chinese Ghost Tale from Mao to Ming, 1981-1381

- 21. Jepp, Who Defied the Stars

- 22. Anthropology, Footnoted: Jared Diamond’s The World Until Yesterday

- 23. “The Tremendous Man of Color!!”

- 24. Levitation: Physics and Psychology in the Service of Deception

- 25. The Appendix , Appendixed.

Francis Bass

Writing, reading, etc..

Play Time: We Are Proud to Present a Presentation about the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as South West Africa, from the German Südwestafrika, between the Years 1884-1915 by Jackie Sibblies Drury

This past semester I needed to fulfill my honors requirements by completing 3 s.h. of honors credit. I wasn’t in any honors classes, so I did this by contracting a creative writing class focused on time, by designing an additional curriculum of nine plays that I would read and respond to—all of them dealing with time in some way. Thus, Play Time —nine essays analyzing specific plays, pulling apart the way the playwrights are using the medium of theatre to manipulate or comment on or distort or theorize about time. The idea isn’t so much to definitively state What X Play is About, but more to point out what I find interesting in the play, and figure out how the artist—or how theatre as a medium—achieved it. This first post is on We Are Proud to Present a Presentation about the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as South West Africa, from the German Südwestafrika, between the Years 1884-1915 by Jackie Sibblies Drury, and I promise I will only use the abbreviation of that title from here on out.

We Are Proud to Present is a play about six actors putting together a theatrical presentation detailing the history of Namibia as a German colony, and the genocide of the Herero people. The play is as much focused on the conquest, exploitation, and extermination of the peoples of Namibia as it is on how the actors are portraying it, how they are trying to relate to it, how theatre operates as a medium, and how to tell the history of a people who were almost completely wiped out.

Processtation

The play (that is, the theatrical work written by Drury) portrays this presentation (that is, the theatrical work performed by the characters in the play) from start to finish in chronological order, though it switches back and forth between “The Presentation” and “The Process” (7). Each scene is labeled as one of the two. “The Presentation” is an actual performance of the presentation, and “The Process” is a rehearsal of it (presumably early on in the production.) So while the audience (that is, an actual real world audience) is seeing the presentation about the Herero of Namibia from start to finish, they are also seeing the actors themselves in two different moments in time. This structure accomplishes a few things.

First, it’s an efficient way to show both the creation of the show and the show itself. The play could’ve been divided into two acts, the first The Process and the second The Presentation, but by interweaving the two into one continuous action, Drury can avoid repetition, and just show the most important pieces of each strand.

Second, it makes it very clear how The Process is being expressed in The Presentation. For example, at one point during rehearsal, the actors are doing an exercise, and Actor 3 is acting as Actor 6’s grandma:

“( ACTOR 3 smacks ACTOR 4 with his prop on each “Tell.” ) “ACTOR 3 ( as Grandma ): Tell me that you didn’t eat that cornbread. … “Tell me that you didn’t eat that corner piece of cornbread. “I don’t need you to Tell me that you ate that corner piece of cornbread. “I can Tell the corner piece is missing so Tell me that you ate it. “Tell me. “Tell me.” (58)

Later on, during the actual performance, the audience sees how the actors have repurposed this theatrical device for a completely different scene, with completely different implications:

“( ANOTHER WHITE MAN lands blows on BLACK MAN on each “Tell.” ) “ANOTHER WHITE MAN: Tell the man you broke the law … “Tell the man you were gonna kill me. “I don’t need you to Tell me that you were gonna kill me. “I can Tell you wanted to kill me, so Tell the man. “Tell him. “Tell him.” (102)

There are echoes, recurrences, like this all throughout the play, and by presenting the rehearsal and the performance in such close proximity Drury examines how the most contentious, the most bizarre, or the most seemingly useless ideas generated during rehearsal are reshaped, retooled, and evolved to express something in the presentation.

Overall, the intertwining of these two threads shows how Process and Presentation are always in conversation, and how the Presentation is still a part of the Process. As the play reaches its climax, it becomes unclear whether the actors are rehearsing by themselves or performing for an audience, with the final scene labeled “Processtation” (97). The actors are all still trying to process, and work out how to express this tragic episode of history, even in its rehearsed, presented form. Although they may be separated in time, Process and Presentation are in fact simultaneous components of one unbroken continuum.

The Tempo of History

When I said the presentation is presented chronologically, that wasn’t entirely accurate. The presentation is presented in the order that an audience (that is, an audience within the world of the play) would see it, but the presentation itself is not perfectly linear. It begins with an overview, a rapid summarization of each year of German South West Africa from 1884-1915. The overview utilizes a simple formula—Actor 6 announces the year, the other actors recite one or two key events, or express the overall sentiment of a certain demographic group, and then Actor 6 announces the next year. This creates a consistent rhythm—a tempo. Each year lasts two to four lines. And with this tempo established, Drury can explore how history is processed, communicated, and perceived.

The best example of Drury staging different perceptions of history is the history of the railroad. Starting in 1895, the Germans begin construction of a railroad. Actors 1 and 3 are white, and represent the Germans. Actor 2 is black, and represents the indigenous people of Namibia.

“ACTOR 6: 1896. “ACTOR 1: We are building that railroad. “ACTOR 3: We are building that railroad. “ACTOR 2: We are building that railroad. “ACTOR 6: 1897. “ACTOR 1: We are failing. “ACTOR 3: We are failing. “ACTOR 2: We are building that railroad. “ACTOR 6: 1898. “ACTOR 1: We are really failing. “ACTOR 3: Not good. “ACTOR 2: We are building that railroad. “ACTOR 6: 1899. “ACTOR 1: We are fucked. “ACTOR 3: So fucked. “ACTOR 2: We are building that fucking railroad.” (18-19)

This portrayal of history shows how history can occur at a different pace for different groups. While the Germans are changing their reaction to the situation with each year, the African laborers building the railroad say (mostly) the same thing each time. History for them does not describe an arc in this time period, it is just a flat line as year in and year out they are performing the same labor. The consistent tempo underscores that, regardless of how the narrative is framed after the fact around those in power, the less powerful are still stuck doing the actual work propelling history forward.

Later during the overview, repetition is used to different effect. In 1904, the genocide of the Herero began, so from 1905 through 1908, the phrase, “The General Issues The Extermination Order” is repeated every year (20-21). The constant rhythm makes this phrase sound like death knell. Even though the extermination order was only issued one time in 1905, its repercussions are echoing through the years, inescapable, unending.

The final twist on the Overview begins with 1908. Actor 6 announces that “Eighty percent of the Herero have been Exterminated,” (21) and after a few more lines of summary, reads out each year from 1909 to 1915. None of the other actors recite lines during these years, and in the script, although there is no punctuation and it is all part of Actor 6’s announcement, each year is followed by a skipped line. After this frantic, high energy, persistent drumbeat of historical points and societal sentiments, the silence is incredibly pronounced. With eight in ten Herero dead, their voices, and their history, have been silenced, and Drury places great weight on this by contrasting the years following the genocide so heavily with the years preceding it.

Drury’s exploration of time is twofold in this play—there is the timeline of a theatrical production, which she plays with by alternating between Process and Presentation, and there is the timeline of history, which she deals with throughout the whole work (though I chose to analyze one specific instance of it with the “overview.”) The play is both an examination of these things, and the things themselves. The conversation between rehearsal and performance started within this play will continue into actual productions, as will the conversations surrounding the portrayal of history. What is so engaging about this play is the fact that it is constantly in dialogue with the reader or audience—in fact, the stage directions themselves are full of attitude, and often ask questions (for example, “ ACTOR 3 becomes Grandma. Not OK. But … pretty good? ” [56].) The play expresses the ping pong nature of history, the way it affects the present and the present affects it, and the plurality of it, and it extends this conversation out to the audience to be carried on after the curtain has fallen.

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, From the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915

By jackie sibblies drury directed by eric ting in association with john adrian selzer, november 7 2012 - december 16 2012, “i’m not doing a german accent you aren’t doing an african accent we aren’t doing accents”, an ensemble of american actors come together to make a play about the little-known first genocide of the 20th century. as the group wrestles with this remote story, their exploration hits much closer to home than anyone ever expected., in her new york debut, drury collides the personal and political, the humorous and harrowing, in this exhilaratingly irreverent play directed by eric ting..

2013 OBIE Award for WE ARE PROUD TO PRESENT…

Eric Ting for Direction

The New York Times

“an inventive new play…incendiary results…We Are Proud impressively navigates the tricky boundaries that separate art and life”

Time Out NY

“Extraordinary…Soho Rep has been brilliantly undesigned…Director Eric Ting and the company turn history into Schoolhouse Rock for the genocidally aware”

“90 minutes of original, enlightening, pulse-pounding theater…It’s absolutely thrilling…it is visceral, fiercely intelligent, and entertaining. We should be grateful to Soho Rep. for showcasing this promising writer, her talented director, and their vital, important play.”

TheaterMania

“A potent mix of laughter and discomfort…Eric Ting’s nuanced direction…particularly powerful…The entire experience is a fascinating peek into the charged group dynamics that can play out in the creation of theater, and the work’s conclusion is likely to leave audiences feeling stunned”

“a stunning exploration of the limits of art…simultaneously funny and disturbing, this is one of the best shows of the year.”

The New Yorker

“a thrilling opportunity to see both a serious new talent developing her voice and what an inspiring director can do to encourage it”

nytheater.com

“not something you often witness in theater…incredibly profound and powerful, leaving an open-gaped audience”

Quincy Tyler Bernstine

Lauren blumenfeld, phillip james brannon, grantham coleman, jimmy davis, creative team, jackie sibblies drury.

Set Designer

Toni-Leslie James

Costume Designer

Lenore Doxsee

Lighting Designer

Chris Giarmo

Sound Designer

Jeff Larson

Projection Designer

David Brimmer

Fight Director

Props Master

Terri K. Kohler

Production Stage Manager

Production Manager

Project Number One was initially launched in 2020 as a job creation program in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and record unemployment in our field. It was also an experiment in prioritizing living wages for artists, even when faced with extraordinary challenges.

Join us for our special 99¢ Sunday performances

Soho Rep is a civic theater that produces ambitious, innovative new works by radical theater makers that go on to future productions around the world.

Sign up for our newsletter, thank you for signing up.

There was an error signing up. Please review your information and try again.

This email has already been signed up for our newsletter. Please use a different email.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Welcome to our presentation. We have prepared a lecture to precede the presentation because we feel that you would benefit from some back-ground information so as to give our presentation a greater amount of context. Yeah. OK, so, the lecture's a lecture but it's not a lecture lecture. We made it fun. Ish. Sort of. Anyway.

We are proud to present a presentation about the Herero of Namibia, formerly known as Southwest Africa, from the German Sudwestafrika, between the years 1884-1915 ... Pdf_module_version 0.0.15 Ppi 360 Rcs_key 24143 Republisher_date 20211015211656 Republisher_operator [email protected] ...

We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, From the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915 by Jackie Sibblies Drury (review) Oona Hatton Theatre Journal, Volume 67, Number 4, December 2015, pp. 713-716 (Review) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi ...

4 T Theat Scoo t DP Unty We Are Proud to Present a Presentation 5 BIOGRAPHIES [cont.] BIOGRAPHIES DRAMATURGY NOTE [cont.] the world premiere of Holly Arsenault's Undo (Annex Theatre, Gregory Award for Outstanding New Play), It's a Wonderful Life (Theatre Anonymous), the world premiere of Paul Mullin's Ballard House Duet (Custom Made Plays/Washington Ensemble

personal in a play that is irreverently funny and seriously brave. We Are Proud To Present . . . premiered off-Broadway at Soho Rep in 2012. This new Modern Classics edition features an introduction by Leonor Faber-Jonker. We are Proud to Present a Presentation about the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as South-West Africa, from the

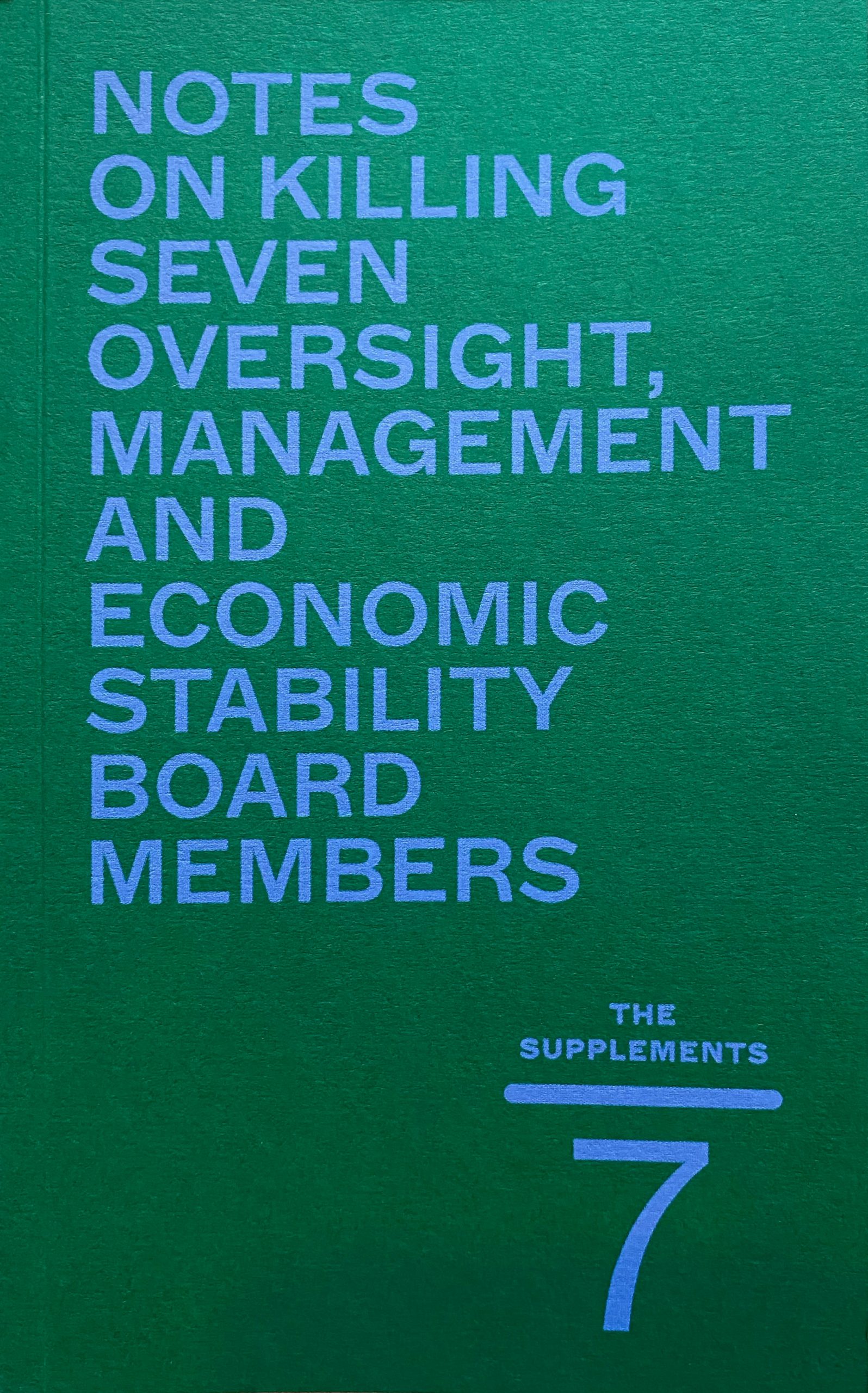

We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, From the German Südwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915 is a 2012 comedy/drama play by the American playwright Jackie Sibblies Drury.

Elsewhere in this issue of The Appendix, we interview the writer Jackie Sibblies Drury about her play We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as South West Africa, From the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915, which earned glowing reviews during its recent runs in Chicago and New York. Its plot is this: six black and white American ...

An!SMSUTheatrepressrelease!describes!"We!are!Proud!to!Present…"!as"powerful, energeticandsurprisinglyfunny."!!! Tickets!for!"We!Are!Proud!to!Present ...

We Are Proud to Present is a play about six actors putting together a theatrical presentation detailing the history of Namibia as a German colony, and the genocide of the Herero people. The play is as much focused on the conquest, exploitation, and extermination of the peoples of Namibia as it is on how the actors are portraying it, how they ...

We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, From the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915 by Jackie Sibblies Drury directed by Eric Ting in association with John Adrian Selzer. November 7 2012 - December 16 2012 ...